From December 2018:

As we celebrate 90 years of Hinkle, we asked professional storyteller and adjunct professor Sally Perkins to share a few stories from its illustrious history. Sally is the creator and performer of “Keeping Hinkle Hinkle,” a story commissioned by Storytelling Arts of Indiana and Indiana Landmarks in honor of Butler receiving the Cook Cup Award for its historically accurate restoration of Hinkle Fieldhouse in 2014.

* * *

What six-year-old wouldn’t want to see Hinkle’s center court from a bird’s eye view?

After all, from one of the 10 trusses that hold up the building, you could see so many “Hinkle Magic” moments: Bobby Plump’s famous last shot in the 1954 Milan High School championship game; the 1955/1956 Attucks High School back-to-back championship games; Butler’s buzzer beater win over Gonzaga in 2013; Butler’s upset win over Villanova in 2017.

And so many not-so-famous “Hinkle Magic” moments: when the women’s team had to fight for their fair share of court time in 1976; when a Butler cheerleader’s boyfriend proposed to her on the Bulldog on center court; when average fans and hundreds of their children got to play on the court, no questions asked, after basketball games.

So many “Hinkle Magic” moments have occurred on that legendary court. But “Hinkle Magic” moments have occurred in other less-expected spaces of the fieldhouse, as well…

Up High

Countless people can tell you they’ve run around that track on the second level of the fieldhouse. But not everyone can say that from that track they successfully distracted Tony Hinkle from his work.

Countless people can tell you they’ve run around that track on the second level of the fieldhouse. But not everyone can say that from that track they successfully distracted Tony Hinkle from his work.

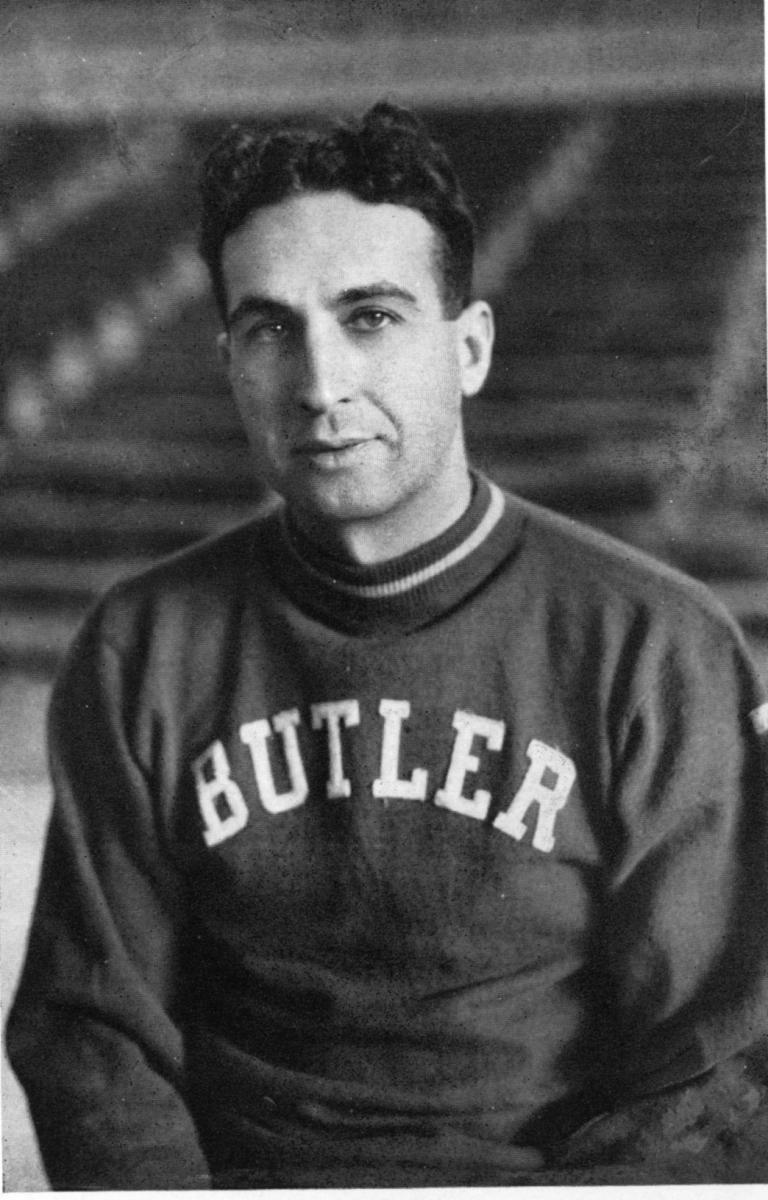

Back in the 1920s, through the 1970s, when Tony Hinkle was the basketball coach … and the football coach … and the baseball coach … and the Athletic Director … and a teacher … he was un-distractible. After all, it takes a person of focus to manage all those roles.

But one day he got distracted.

In the 1930s, Tony Hinkle typically came to the fieldhouse on Sunday afternoons to review film from the previous day’s game. Often, he brought his daughter Patty with him. She thought the fieldhouse was her private playground.

One particular Sunday when Patty was about 6 years old, she roller skated up and down the ramps, got bored with that, then decided she wanted to see what center court looked like … from a bird’s eye view.

So Patty went up to the track on the second level and started crawling up one of the trusses, getting herself halfway to center court. That’s way up there.

Now, every so often, Mr. Hinkle thought he should probably check up on his daughter Patty. So he started looking around the fieldhouse. When he couldn’t find Patty, he stepped into the arena.

Maybe he heard a sound; maybe he just moved his head the right way, but he looked up and there he saw his 6-year-old daughter, like a sloth crawling out to center court. Gulp.

Lucky for Patty, her father wasn’t, well, Bobby Knight. Mr. Hinkle knew that yelling at Patty would likely scare her to her death. So he called the fire department, who raced over to the fieldhouse with a net.

But Patty thought to herself, “Eh, if I can get myself out here, I can get myself back.” So she started crawling backwards along the truss, sliding down its arc until she landed on her feet, on the track … right across from her father. Patty stared at her father’s feet.

They stood in silence for a long time.

Until finally Mr. Hinkle said, “You got guts, don’t ya, kid?”

He never said another word. And he never told her mother. A secret “Hinkle Magic” moment Patty and her father shared for the rest of their lives.

But that wasn’t the only time something on that track distracted Tony Hinkle.

On Track

In 1946, Charlie McElfresh—a man who was tiny enough to be a horse jockey—came to the fieldhouse when Mr. Hinkle hired him to be his equipment manager. Frankly, it was a low-paying job, but Charlie knew it meant his kids could come to Butler tuition-free. So he took the job and spent the next 33 years of his life down in the bowels of the fieldhouse in the equipment cage, which isn’t so unlike a jail cell: crowded, dark, cramped … odorous.

But Charlie rather preferred life down there. He always had a six-inch cigarette holder hanging out of his mouth as he washed and dried every football, basketball, and baseball uniform, game after game after game.

Now if you met Charlie, you might wonder if he liked the athletes. Or any humans, for that matter.

His rather crass nature was especially obvious one day in the 1970s when the men’s basketball team went to Omaha for a game against Creighton. On this rare occasion, Charlie got to travel with the team.

The coaches and Charlie stayed up a little too late on Friday night in Charlie’s room playing poker. The next morning, all the team members and coaches were gathered for breakfast in the hotel lobby as the players all stuffed themselves with scrambled eggs and bacon before the game. But Charlie was nowhere to be seen.

One of the players asked, “Where’s Charlie?”

Knowing how small Charlie McElfresh was, one of the tallest players on the team, John Dunn, joked, “Heh. Heh. Maybe he couldn’t figure out how to jump out of his bed this morning!”

They all laughed and hollered until John Dunn happened to turn around, and there he stood face-to-face (well, chest-to-face) with Charlie, who barked, “Wash your own damn clothes, Dunn.”

And John Dunn did have to wash his own clothes for the next three weeks until Charlie was ready to forgive him. Charlie was nobody’s servant down there in the equipment cage.

But Charlie McElfresh was looking out for those boys. Whenever he thought Mr. Hinkle’s practices had gone on too long, or that Mr. Hinkle was being too tough on the boys, Charlie would put on a giant cowboy hat he had in his equipment cage. Then he’d hop onto an old banana seat bicycle that was hanging around in the fieldhouse. He’d ride that bicycle up the ramp to the second floor, where he’d ride around and around the track, wearing that huge cowboy hat until everyone would look at him and laugh. Finally, Mr. Hinkle would say, “Alright, alright Charlie. I get it. I get it.” And practice would end.

So once again, the un-distractible Tony Hinkle was distracted by a “Hinkle Magic” moment on that track on the second floor.

Down Low

There are a lot of Charlie McElfresh “Hinkle Magic” moments. Most occurred away from public view, deep down in the equipment cage, in the depths of Hinkle Fieldhouse.

There are a lot of Charlie McElfresh “Hinkle Magic” moments. Most occurred away from public view, deep down in the equipment cage, in the depths of Hinkle Fieldhouse.

Back in 1976, when the United States was celebrating its bicentennial, Barry Collier was a student athlete at Butler, mourning the loss of his final basketball game his senior year. It was an away game. So when the team got back to Butler, the bus pulled into the fieldhouse parking lot, and the boys were told to go turn in their uniforms.

The team members all trudged down, down, down to the equipment cage. Barry lingered behind the rest of the team. Finally, with his chin sagging to his chest, he tossed his uniform into the bin and took some melancholy steps out of the equipment cage.

Suddenly he heard a raspy voice behind him say, “Check the ice machine before ya leave.”

Barry spun around. “What? What, Charlie?”

“CHECK THE ICE MACHINE BEFORE YA LEAVE,” Charlie growled.

“Uh, alright. Alright. Sure, Charlie.”

So Barry walked over and opened the refrigerator door. In the ice box sat a single item: a brown paper bag with a six-pack of Stroh’s beer.

Barry spun around to say, “thank—” but Charlie was gone. He smiled, took out the six-pack, and went to find a fellow senior teammate to share it with.

A “Hinkle Magic” moment from Charlie McElfresh.

Four years after Barry Collier graduated, on a September Sunday in 1980, Charlie McElfresh was washing and drying football uniforms when he had a heart attack and died in that equipment cage. That cigarette holder hanging out of his mouth.

He wouldn’t have wanted to have been anyplace else.

Why? Because Hinkle Fieldhouse is filled with “Hinkle Magic.” If you look hard enough and listen to enough stories, you’ll find that magic not just on the court, but in the nooks and crannies, the bowels and cages, the tracks and bleachers … and mostly in the hearts of the people who dedicate their souls to one another in that special space we call Hinkle Fieldhouse.