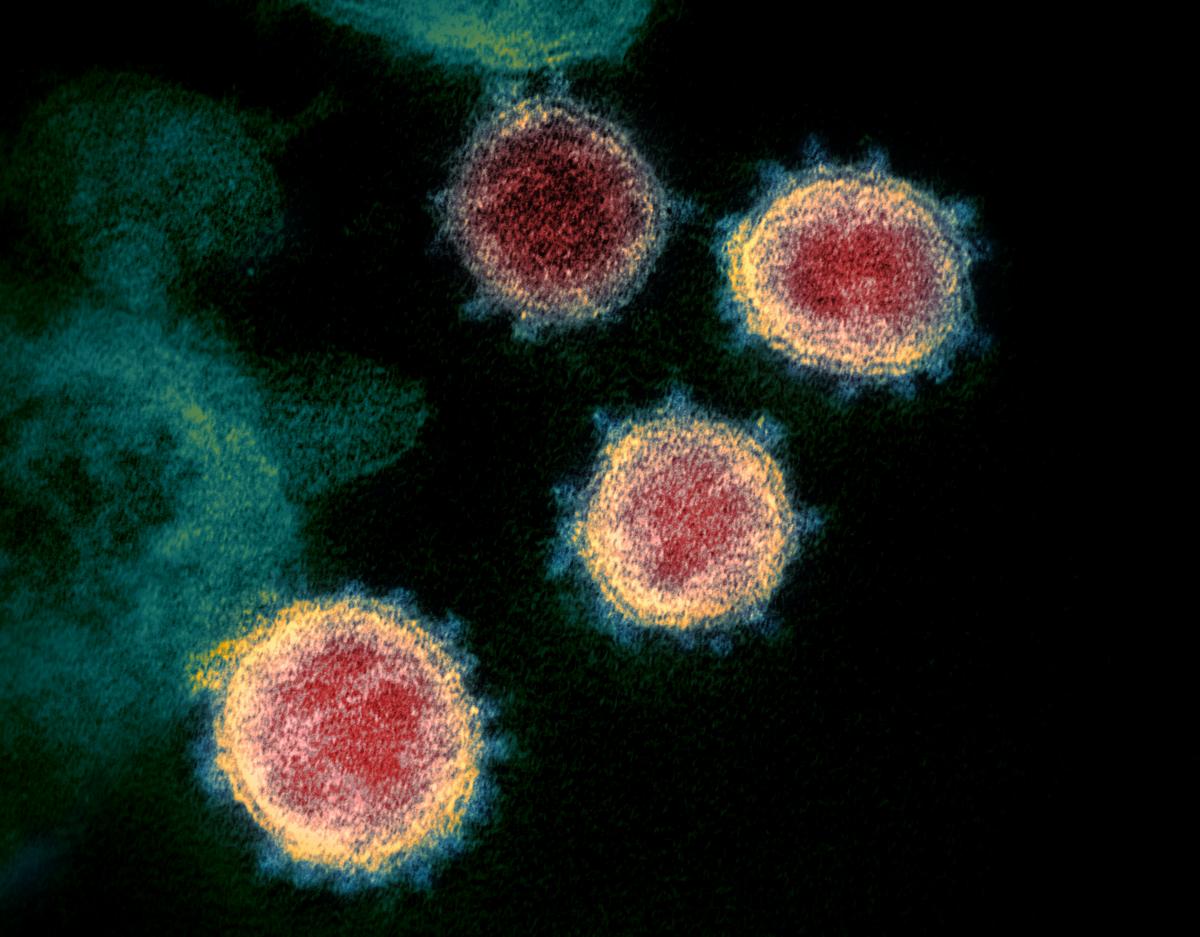

Over the past year, you’ve probably seen images flooding the news of floating spheres covered in spikes—an up-close view of the microscopic particles that cause COVID-19. The depictions provide a concrete visual for something otherwise abstract to most people.

That’s all thanks to a team of artists at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)—part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH)—where Austin Athman ’09 works as a Visual Information Specialist.

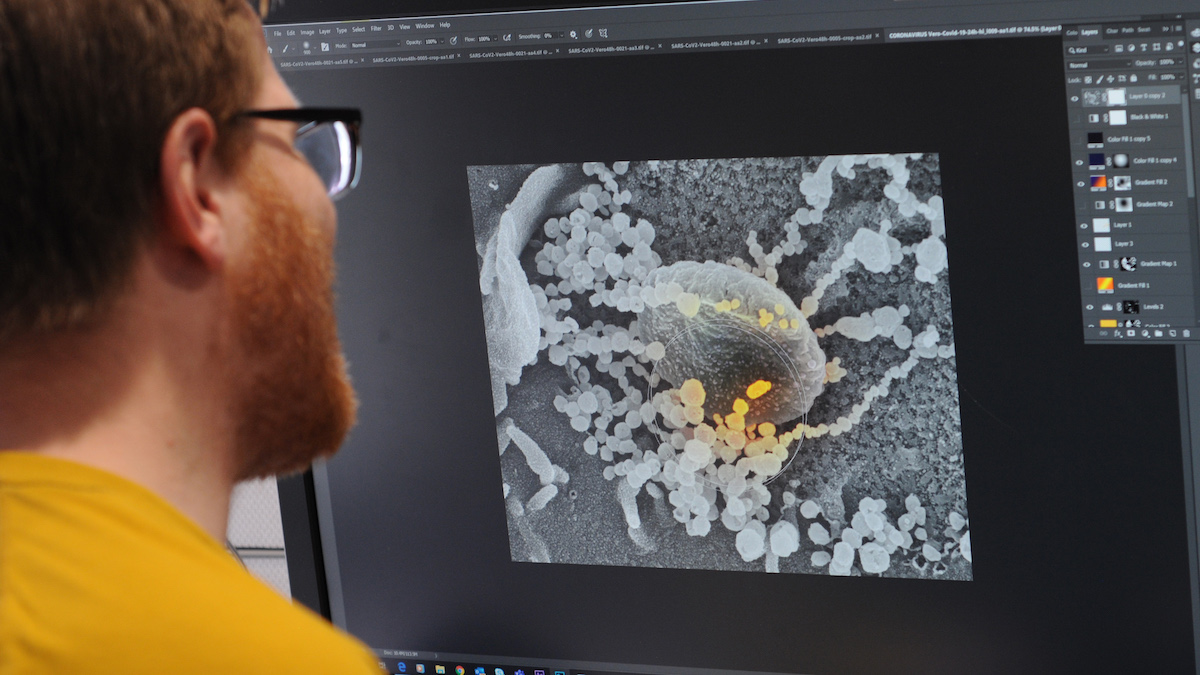

At Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton, Montana, science and art collide. After high-power microscopes capture black-and-white images of disease samples, Athman and his colleagues use digital tools to add colors and details that bring the photos to life.

The end result is a colorized image that helps scientists better understand the virus particles—which are about 10,000 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair—as well as put a face to a top enemy for the general public.

When COVID-19 arrived in the United States, Athman’s lab received a sample of the coronavirus from one of the first patients.

“As soon as we had the sample,” Athman says, “we started taking pictures, colorizing them in Photoshop, and putting them on the NIAID Flickr website. The next day, we already saw the images being used by major news outlets across the country.”

Athman starts by sitting down with scientists and microscopists to learn more about what he’s looking at in the black-and-white photo.

“If I can get a scientist to explain what something looks like in common language,” Athman says, “it helps people outside the lab understand something about science in a way words can’t always do.”

Athman wants viewers to look at the most important part of the image, and that’s where art comes in. He starts by adding highlights and shadows that bring depth to the otherwise flat-looking photos. He also rotates and crops the images in a way that guides the eye to desired focal points.

Then comes the color. The scientists and artists don’t know what the particles’ true colors are, or if the diseases even have color. But they choose palettes that make the photos more engaging and understandable while still appearing realistic.

While Athman has always enjoyed science, he majored in Music and Multimedia Studies at Butler. However, after a high school internship in graphic design at the NIAID, followed by summer jobs there every year throughout college, he accepted a permanent position upon graduation and has been at the lab ever since.

“Recently, I’ve been focusing on the COVID-19 images,” Athman says about his day-to-day work. “But when we aren’t in pandemic mode, I do all kinds of visual things. I draw illustrations, design graphs, edit videos, and create scientific animations. It’s a new thing almost every day. And this merge of art and science—I think a lot of people aren’t really aware this kind of field exists.”

Photos courtesy of the NIAID