This story is part of a mini-series exploring The Farm at Butler, its methods, and its mission. Part three of six.

The Farm at Butler probably looks different from any you’ve seen before. It’s not a wall of corn or wheat, the same crop filling miles of fields along the highway. Instead, the one-acre space—nestled on a floodplain between the White River and the Central Canal—looks more like a backyard garden. Plenty of space separates each of the long, narrow plant beds growing more than 70 kinds of plants, and woody shrubs crawl up the sides of a wood-plank fence. You won’t see a tractor here, or even a plough—all the work is done by hand. And with just one full-time farmer and a handful of student interns, there aren’t that many hands to do the work.

Still, The Farm produces about 10,000 pounds of food each year.

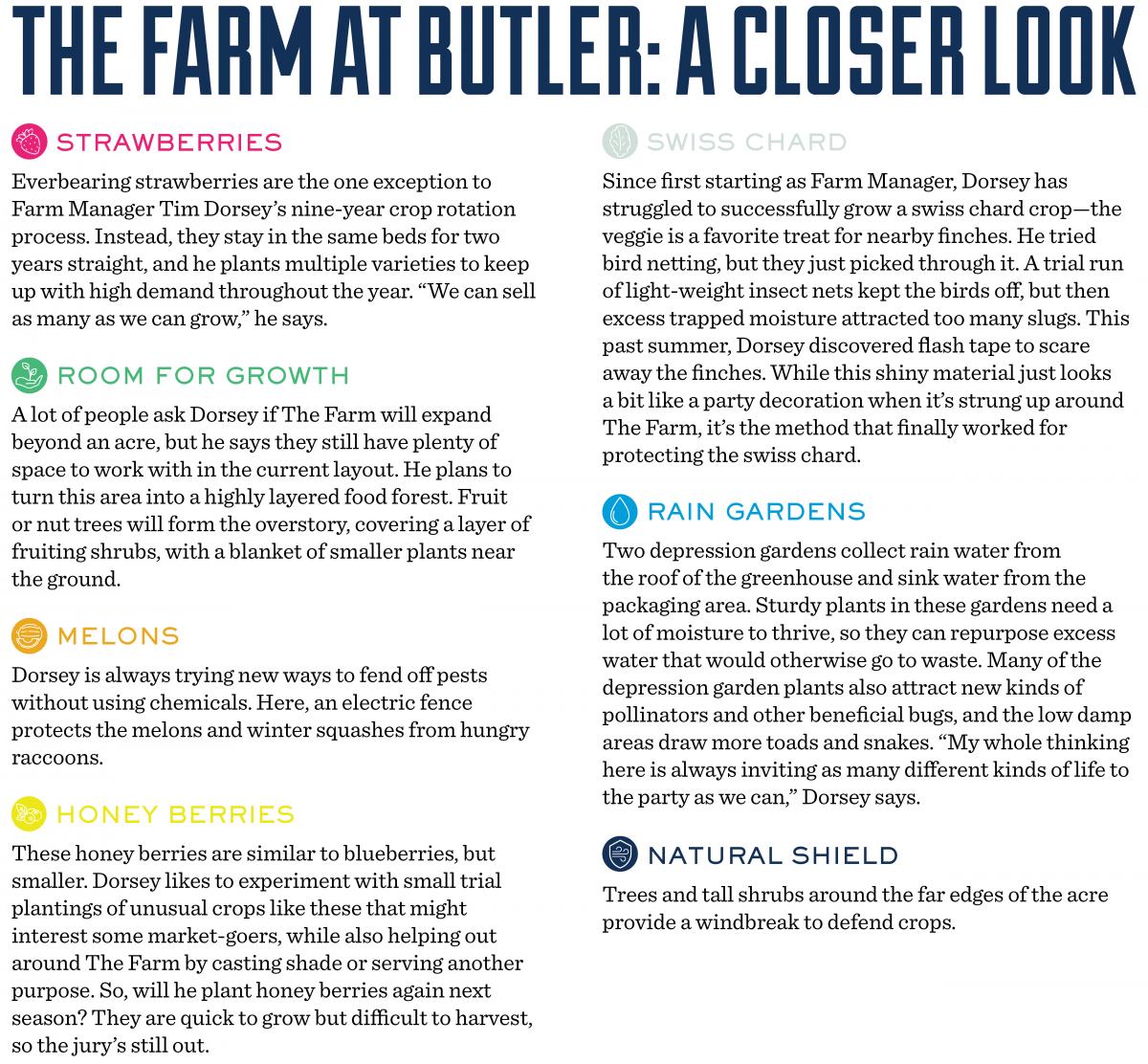

That’s because Farm Manager Tim Dorsey and other leaders in Butler’s Center for Urban Ecology and Sustainability (CUES) have decided to let nature do the heavy lifting. Below, learn more about how nearly every aspect of The Farm at Butler draws from other ecosystems for guidance on how to make the most of organic growing.

Agroecology:

The Farm is built on the idea of agroecology, a way of farming that looks to natural ecosystems for inspiration. Dorsey uses the forests and prairies surrounding The Farm as a guide, mimicking what he sees to create a diverse environment. For example, he tries to plant in a variety of layers, and he grows a mix of perennial and annual plants.

Dorsey has recently focused on adding more perennial permaculture elements, such as sturdy trees and shrubs, which live for years instead of requiring replanting each season. In addition to layering the canopy and providing shade as they grow, these more stable, low-maintenance plants minimize soil disturbance. Dorsey says this sort of farming is even healthier for the ecosystem than basic organic growing.

Caring for the soil:

A key element of sustainable, organic farming is protecting soil health. The more stable the soil, the less erosion and run-off will occur, the less pollution will take place, and the healthier the plants will be. At The Farm, Dorsey protects the soil in a variety of ways. For example, The Farm is on a nine-year crop rotation plan, which means a plot of soil grows a different plant each year for nine years. This gives the soil time to replenish itself with specific nutrients that were drained by previous plants. Some deep-rooted plants also serve the purpose of capturing the nutrients that have sunk to the lowest layers of the soil, then redistributing them to the upper layers, which helps make sure every nutrient gets used. And between plantings of different crops, they don’t use chemicals to kill remaining plants—they just lay down straw to smother out sunlight and conserve moisture.

During the winter, or when there is any gap in the regular rotation, Dorsey plants cover crops to keep the soil in shape. For example, as soon as they finished harvesting the onions this summer, they put in oats. Oats will grow a lot before winter, and they also have an extensive root system. Onions get the most fertilizer (from compost), and oat roots scavenge what’s left so that nothing is wasted. Then when the oats die in the winter, they easily become automatic mulch, making it easy to handle in the spring.

Making the most of bugs:

Most people understand the importance of pollinators such as bees and butterflies when it comes to growing a garden, and The Farm is always looking for ways to put nature’s workers to the task. Two bee hives on The Farm are home to many of its buzzing friends, and a plot of flowers—which are later sold at the market—attract several graceful butterflies at a time. When deciding which new crops to try, Dorsey often focuses on choosing ones that serve a secondary purpose of bringing in more good bugs. “If we can get things to perform more than one function,” he says, “that’s ideal.”

But some critters making their way onto the acre aren’t so friendly—some pests gnaw at the leaves and plant their eggs on the stems. So Dorsey also makes sure to use “companion planting,” incorporating flowering plants that attract the right predatory insects to kill the pests. You might think of a wasp as a nuisance—or just plain evil—but on the farm, it serves a useful purpose.

What grows on the farm?

| Apples | Cilantro | Lemongrass | Raspberries |

| Arugula | Collard | Lettuce | Rhubarb |

| Asparagus | Corn | Melons | Rosemary |

| Basil | Cucumbers | Mint | Rutabaga |

| Beans | Dill | Mustard | Sage |

| Beets | Dwarf Korean pines | Onions | Scallions |

| Bok Choy | Eggplant | Oregano | Spinach |

| Broccoli | Fennel | Parsley | Squash |

| Brussels Sprouts | Flowers | Peas | Strawberries |

| Cabbage | Garlic | Peaches | Sunchokes |

| Carrots | Gooseberries | Peppers | Sweet corn |

| Cauliflower | Hazelnuts | Peppermint | Thyme |

| Celery | Honeyberries | Potatoes | Tomatoes |

| Chard | Kale | Pumpkins | Turnips |

| Chives | Leeks | Radishes | Watermelon |

READ MORE:

Part 1: Getting To The Root of It: How Butler’s One-Acre Farm Has Evolved In a Decade

Part 2: Farming Full-Time: How Tim Dorsey Discovered the World Through Agriculture

Part 3: A Crash Course on Nature-Focused, Hands-In-The-Dirt Growing

Part 4: Sustainability on the Syllabus

Part 5: A Model for Urban Farming in Indianapolis

Part 6: So, Where Does All The Food Go?

Explore the full Farm at Butler mini-series here

Media Contact:

Katie Grieze

News Content Manager

kgrieze@butler.edu

260-307-3403 (cell)

Innovations in Teaching and Learning

One of the distinguishing features of a Butler education has always been the meaningful and enduring relationships between our faculty and students. Gifts to this pillar during Butler Beyond will accelerate our commitment to investing in faculty excellence by adding endowed positions, supporting faculty scholarship and research, renovating and expanding state-of-the-art teaching facilities, and more. Learn more, make a gift, and read other stories like this one at beyond.butler.edu.